Swifties, this one’s for you. It seems like Taylor Swift's Eras Tour has lasted eons. Yet somehow, there’s always something to talk about. Just thinking about how much she’s accomplished while on tour makes me want to buckle down, lock in, and channel my inner girlboss. But while I can’t even be bothered to cook dinner at home after a long day of work, Taylor is accomplishing milestones most musicians can only dream of. Let’s recap.

The Era’s Tour began in March 2023 with its North American leg. It’s set to go until December 2024, with dates in Europe, Australia, Asia, and South America— spanning 152 shows across five continents.

As the queen of multitasking, Swift hasn’t stopped at just selling out stadiums. Since the Eras tour began, she’s released multiple albums — both new and old — and shaken up the tour setlist with each new release. Her list of new releases started on the first day of tour with “All Of The Girls You Loved Before,” which was quickly followed up by “The Alcott,” a feature on The National’s album — reciprocity for their work on her pandemic era albums, Folklore and Evermore.

She also released Midnights: Late Night Edition (including the iconic collab with Ice Spice), as well as not one but two album re-releases — Speak Now Taylor's Version and 1989 Taylor's Version. As if that wasn’t enough, she announced her latest album, The Tortured Poet’s Department, in a GRAMMY’s acceptance speech. Talk about legendary. Since its release, she’s also been churning out deluxe versions and remixes to keep us on our toes. The Eras Tour was even made into a Blockbuster film that brought Beyonce to its premiere. Star power: confirmed.

But that’s just her work life. Her personal life is just as eventful. She ended her 7-year relationship with Joe Alwyn in April 2023. Then entered into a brief but controversial fling with 1975 frontman Matty Healy. Though it didn’t last long, the relationship was enough to inspire a whole album and catapult her into her current romance with Travis Kelce, aka Amerca’s first nepo boyfriend. Now they’re the American Royal couple — and she somehow had time to fly from tour to his Super Bowl performance.

We all have the same hours in the day as Taylor Swift, but how she uses them will always be a mystery to me. I work eight hours a day and can barely manage a social life. Meanwhile, Taylor literally has it all — though conservatives are turning on her for daring to be a woman in her 30s who’s not married with kids. If that’s not proof that women can’t do anything right, I don’t know what is.

Clearly, she’s working late because she’s a singer. No wonder Taylor Swift became a billionaire months into her tour in October 2023. Her net worth is currently around 1.3 billion dollars, making her the only female musician to become a billionaire from her music.

Other entertainment billionaires like Rihanna, Kylie Jenner, Kim Kardashian, Jay-Z, and Kanye West have joined the three-comma club thanks to ventures like clothing brands, beauty products, and other entrepreneurial pursuits. Rihanna has her FENTY Empire. Kim has her award-winning SKIMS. Ye had Yeezy. But Taylor has an unbeatable catalog of publishing.

But Taylor isn’t just different from other Billionaires because of how she earned her money. She’s the Taylor we know and love because of how she spends it. Her rollercoaster Eras Tour is how she’s made much of her fortune. And she’s using it to give back in monumental degrees. From individual donations to investing in local infrastructure, Taylor is literally changing lives on a macro and micro scale. And teaching us what to expect from all billionaires in the process.

The Era’s Tour Bonuses — Talk About Workplace Benefits

First to make headlines were the Eras Tour crew bonuses. While some of us get rewarded with a pizza party or a $10 gift card to Starbucks, Taylor casually dropped $55 million in bonuses for her tour crew. The massive sum was paid out to everyone who makes the Eras Tour go around, from truck drivers to dancers and sound technicians.

In fairness, these bonuses are definitely well-deserved. Taylor’s shows are over three hours long. Imagine dancing for that long — because Swift certainly isn’t the one with the impressive moves — for hundreds of tour dates. Or remembering countless combinations of light cues to go with a setlist that changes daily. Yeah, they’re clocking in. And if my boss had millions to blow, I’d be expecting a comfortable bonus too. But $55 Million? That’s a testament to Swift’s generosity. It's like she's Oprah, but instead of cars, she's giving out life-changing amounts of cash. "You get a bonus! You get a bonus! Everybody gets a bonus!"

It’s similar to how Zendaya gave film equity to every member of the crew that worked on her controversial black-and-white drama, Malcolm & Marie. Filmed in a few days with a bare-bones crew during the peak of the pandemic, the film was Zendaya’s passion project with Sam Levinson, in which she starred alongside John David Washington. Though the film got mixed reviews, it captured the audience’s attention all the same. After all, it was Zendaya — and we’ll watch her in anything. So since the film sold to Netflix for a hefty sum, all the crew members got payouts from the deal on top of their salaries to reward their hard work.

Bonuses and equity payouts are common in many industries, but not entertainment. Even though it’s one of the most lucrative and recognizable American industries, most entertainers don’t make enough to survive. The SAG and WGA strikes last year were proof that there needs to be systemic change in the industry. LA County has even identified show businesses as risk factors for being unhoused — after all, how many stories do we hear of actors who were living in their cars before their big break? And for many, their big break never comes. For even more, they get hired on amazing gigs with giant performers … then go right back to the grind afterward. While individual actions from our favorite stars won’t fix everything, Zendaya and Taylor are providing models for how Hollywood should treat the people who make this town go round.

And in this economy, even a little bit could go a long way. Inflation and the cost of living are not a joke. Especially when, like with many creative careers, you often have to invest in lessons or equipment for your craft. With all this considered, the impact of Swirt’s donations can’t be overstated. Imagine getting a lump sum of cash for dancing to your favorite Taylor Swift tracks? Talk about a dream job.

The Economic Impact of Swift - Swiftonomics, if you will

Like Barbie and Beyonce last year, Swift is still on a tear to boost the economy of the cities she’s in just by traveling there — ad inspiring others to make the trek, too.

The Barbie movie proved that by marketing to women (instead of just making Marvel flops like Madame Web that aren’t really targeted to women at all), the entertainment industry can make giant profits. Barbie fever went beyond the theater. Thanks to a plethora of product collabs, the phenomenon rippled through retail.

Similarly, Beyonce’s Renaissance Tour tour generated an estimated $4.5 billion for the American economy. According to NPR, that’s almost as much as the entire 2008 Olympics earned for Beijing. People were taking money out of their 401ks to pay for Beyonce tickets and the glittery, silver-hues outfits to rock at her shows. Cities even started calling her effect the “Beyonce Bump.”

Swift has the same effect. She’s not just proving her generosity on a micro-scale for the people close to her, she’s having actual, tangible effects on the economy. It's like she's leaving a trail of dollar bills in her wake, and cities are scrambling to catch them like it's a country-pop, capitalist version of musical chairs.

The US Travel Association called it the Taylor Swift Impact after she generated over $5 Billion in just the first 5 months of the Eras Tour. But how does this work? It’s not like Taylor is printing more money at those shows, but it almost is. Her tour dates are pretty much economic steroid shots for local businesses. Hotels are booked solid, restaurants are packed, and let's not even get started on the surge in friendship bracelet supplies.

“Swifties averaged $1,300 of spending in local economies on travel, hotel stays, food, as well as merchandise and costumes,” say the US Travel Association. “That amount of spending is on par with the Super Bowl, but this time it happened on 53 different nights in 20 different locations over the course of five months.” That’s not to say anothing of her effect on the actual Super Bowl and the entire NFL season thanks to her ball-throwing boyfriend.

It's like she's created her own micro-economy, and everyone's invited to the party. And unlike some economic theories that rely on wealth trickling down (spoiler alert: it doesn't), Taylor's wealth is more like a t-shirt cannon or the confetti at her shows — showering everyone around.

Donations that actually do good

Taylor isn’t just stepping into cities and calling it a night. She’s also not just throwing pennies at problems - she's making significant contributions that are changing lives. And more importantly, she's using her platform to encourage her fans to do the same.

She kicked off her tour with quiet donations to food banks in Glendale, Ariz., and Las Vegas ahead of the Eras Tour. Once the tour was in full swing, she continued this practice. In Seattle, she donated to Food Lifeline, a local hunger relief organization. In Santa Clara, she showed some love to Second Harvest of Silicon Valley. And let's not forget about her $100,000 donation to the Hawkins County School Nutrition Program in Tennessee.

She’s been making similar donations overseas. Taylor Swift donated enough money to cover the food bills for an entire year across 11 food banks and & community pantries in Liverpool. Swift also covered 10,800 meals for Cardiff Foodbank and many more banks across the UK and EU. Her impact is so profound that her numbers are doing more to combat issues like hunger than the government.

Can billionaires actually be good?

One thing about me, I’m always ready and willing — knife and fork in hand — to eat the rich. Because fundamentally, can any billionaire really be good? In our late-stage capitalist horror story, the answer is usually no. Look how many of them are supporting the Trump campaign just to get some tax breaks.

But here's the thing - Taylor Swift might just be the exception that proves the rule. She's not perfect, sure. She still flies private jets and probably has a carbon footprint bigger than Bigfoot. But unlike most of the others in her tax bracket, she's not flaunting her wealth like it's a personality trait.

Take a look around. We've got billionaires trying to colonize Mars instead of, I don't know, helping people on Earth. In this context, Taylor's approach is more like Mackenzie Scott’s — Bezos’s ex-wife. She's not trying to escape to another planet - she's trying to make this one better.

And look, I'm not saying we should stop critiquing billionaires or the system that creates them. But she's just setting the bar for what we should expect from all billionaires. She's showing us that our collective power as fans can translate into real-world change. That our love for catchy choruses and bridge drops can somehow, improbably, lead to food banks getting funded and crew members getting life-changing bonuses.

So sorry to my neighbors who hear me belting “Cruel Summer” and “right where you left me” at the top of my lungs (and range). Just know it’s for the greater good.

Maine Democracy Gets an Upgrade

While most of America teeters on the edge of a fascist abyss, Maine has given democracy a much needed upgrade with the switch to ranked choice voting.

Maine will officially become the first-ever state to use ranked-choice voting for a presidential election, the state's Supreme Court ruled this September.

This will allow voters to rank each presidential candidate in order of preference for the November election. Voters will now be able to rank all five presidential candidates that will appear on the ballot, which include Republican President Donald Trump, Democrat Joe Biden, Libertarian Jo Jorgensen, Green Party candidate Howard Hawkins, and Rocky De La Fuente of the Alliance Party. But why is ranked choice voting such a big deal?

How Does It Work?

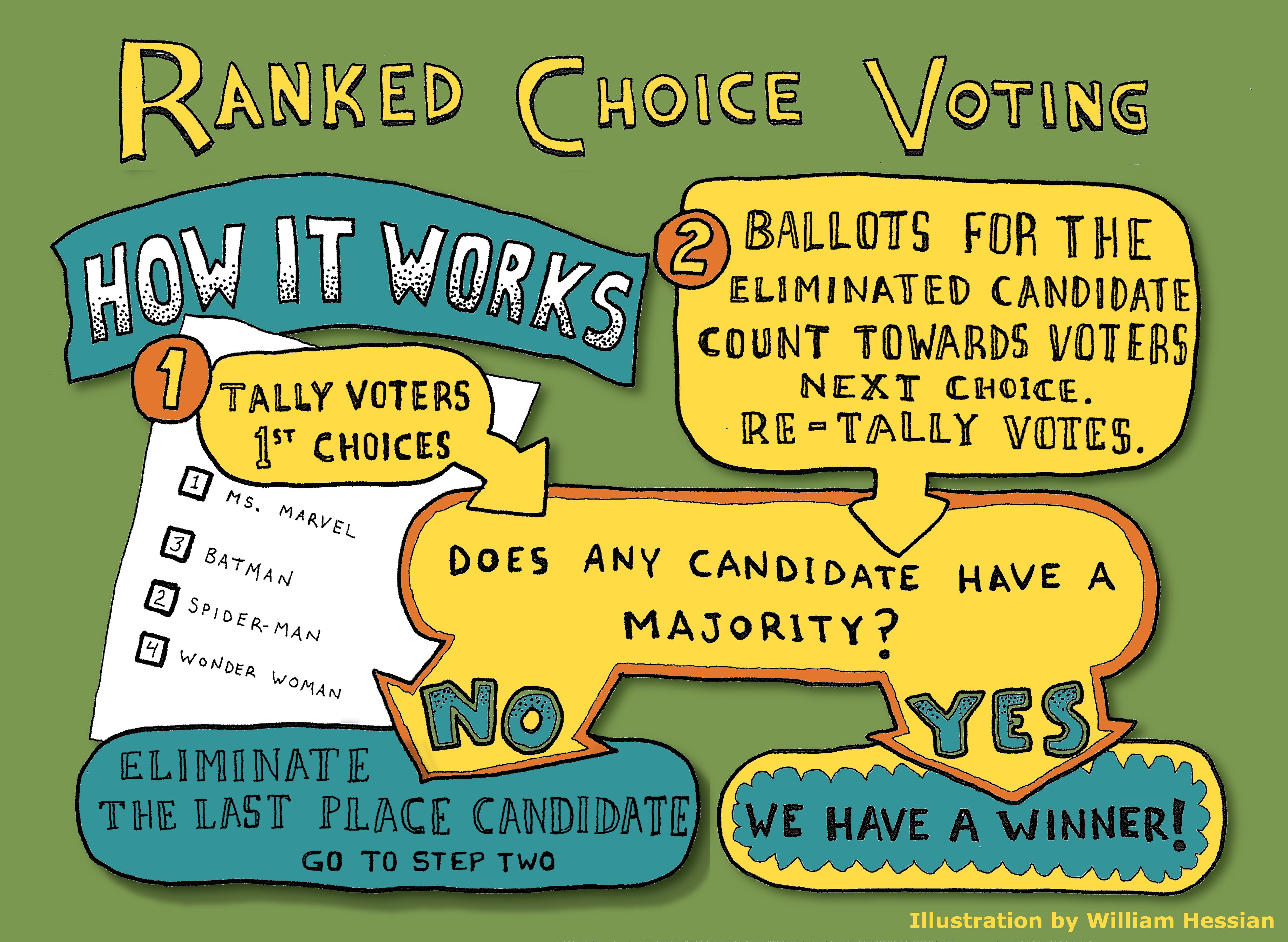

Ranked Choice Voting is also known as instant-runoff voting (IRV), the alternative vote (AV), or preferential voting. In ranked choice voting, instead of only voting for one candidate, voters can rank the candidates in order of preference. You can rank as many or as few of the candidates as you like and leave the rest blank. If any candidate has more than half of the vote based on first-choices, that candidate wins. If not, then the candidate with the fewest votes is eliminated and their votes are redistributed to their second-choices. The process repeats until one candidate has a majority.

Former Massachusetts gubernatorial candidate, Evan Falchuk, explains that ranked choice voting is essentially the same idea as runoff elections. "You hold an election one day, and then you see how the votes come out, and then you eliminate the candidates that didn't meet whatever the threshold is, and then you hold another election. With ranked choice voting, you do that instantaneously," he stated. Maine's new policy is essentially a more efficient way to hold multiple rounds of elections at the same time.

This system was successfully used by all voters in four states in the 2020 Democratic Party presidential primaries, and is used for local elections in more than 15 US cities and the state of Maine. Even some of the biggest critics of RCV agree it's better than our current system.

But what does this mean for elections? Elections have become increasingly unreliable at selecting policymakers who are representative of and supported by their constituents. But RCV eliminates a few of the common problems that exist in our current system. It makes third parties viable, it enables winners that have majority support, and it reduces polarization and negative campaigning.

Benefit # 1: RCV Makes 3rd Parties Viable

The majority of the country uses a system called winner-take-all voting or first-past-the-post voting. In this system, voters each have a single vote which they can cast for a single candidate. Whoever gets a plurality of the votes wins all of the representation. Winner-take-all voting systems naturally trend towards two parties. This is mainly because voters feel that they have to strategically vote for candidates who have the best chance of winning so that they don't "waste their vote."

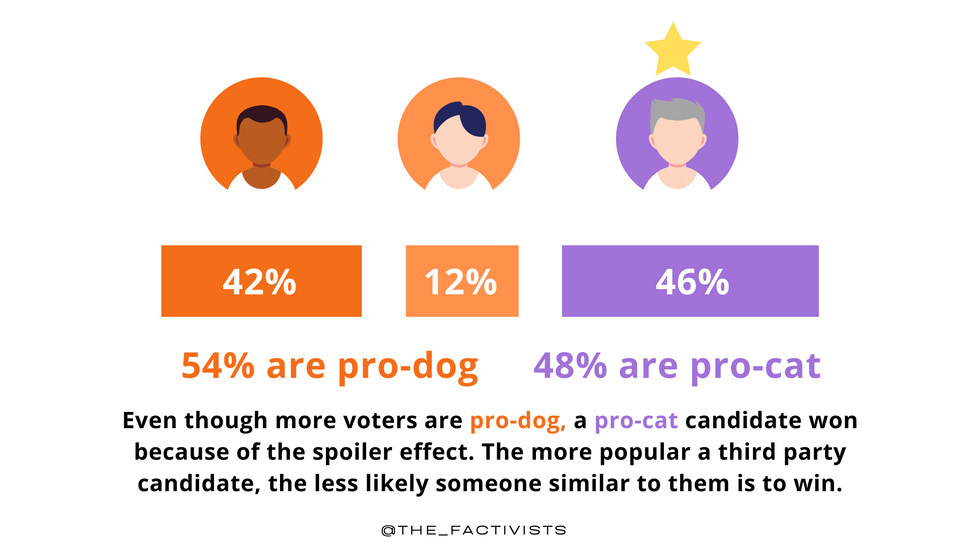

Yet third parties still run for president every four years, and every four years they lose. Sometimes they gain a fair amount of votes, but even then, they are accused of being spoilers.

The spoiler effect is when a third-party candidate's presence in the election draws votes from a major-party candidate similar to them, thereby causing a candidate dissimilar to them to win the election. The more popular a third-party candidate, the less likely someone who has similar beliefs is to win.

The spoiler effect is particularly relevant in close elections like the 2000 presidential race. Many people think that Democrat Al Gore lost the 2000 Presidential Election to Republican George W. Bush because some voters on the left voted for Ralph Nader of the Green Party. If even 1% of Nader's Floridian supporters had chosen to vote for environmentalist Gore over Texas oilman Bush, Gore would have been elected president.

RCV eliminates this issue. Voters can feel confident voting for a third-party candidate, even one they think is unlikely to win, without fear of being a spoiler. Say you live in Maine and you think Green Party candidate Howard Hawkins is awesome, you think Joe Biden is just okay, but most of all you want Donald Trump to lose. Normally, most people would tell you to just suck it up and vote for Biden, because Howard Hawkins is never going to win and it's more important to prevent Trump from winning. With RCV you can confidently rank Hawkins as your first choice and Biden as your second, and you can know that if Hawkins loses, your vote will still be put to good use.

This allows third parties to form and grow because voters can vote for the candidate they like the most without worrying that they will help elect the candidate they like least. If it were implemented across America, RCV may not lead to many third-party wins in the first few years, because America is firmly entrenched in a two-party system. However, RCV allows third parties to gain real footholds and eventually even majority support.

Benefit #2: RCV Enables Majority Support

One of the biggest problems with our current election system is that in order to win candidates only need a plurality of the vote, not a majority. A plurality just means that a candidate received more votes than everyone else, whereas a majority is 51%. This is not a problem when there are only two candidates, but any time there are more than two this becomes a concern.

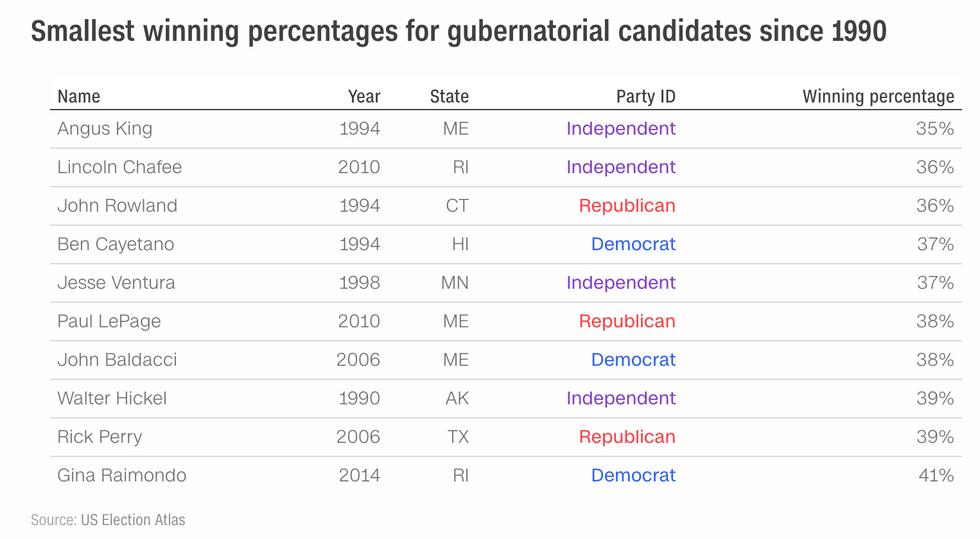

Too often, candidates win elections despite being opposed by the majority of voters. In elections with more than two candidates, candidates can and do win even when less than half of voters support them.

This lack of majority support is part of what pushed voters in Maine towards adopting a new system. For example, in Maine, nine of the eleven gubernatorial elections between 1994 and 2014 were won with less than 50% of voters' support. Maine governors with low winning percentages include Angus King, who won the governorship in 1994 with just 35% of the vote; John Baldacci, who won in 2006 with just 38.1% of the vote; and Paul LePage, who won in 2010 with 37.6% of the vote.

These low percentage wins are not unique to Maine. A recent win in the Massachusetts Fourth Congressional District Democratic primary made headlines when Jake Auchincloss won with only 22.5% of the vote.

RCV has the potential to resolve these issues. With RCV, a candidate can only be declared a winner if they have received 51% of the vote. It's true that not every voter will get to see their first choice candidates win, but a majority of voters will see a candidate they at least somewhat agree with in office. If a voter's first choice is eliminated, their vote instantly goes to their second choice. That way, we can find out which of the top candidates has the most support.

All that being said, RCV will elect a majority winner—so long as that majority winner exists in the election. In RCV you only have to rank as many candidates as you like. This can result in something called exhausted ballots. Ballot exhaustion occurs as part of RCV when a voter has ranked only candidates that have been eliminated even though other candidates remain in the contest. For instance if your ballot just ranks the Green Party and Libertarian Party candidates, but you decided not to rank any of the major party candidates, it's very possible that both of the candidates you voted for will be eliminated therefore your vote won't end up counting in the final round. RCV makes a majority more likely but no single-winner voting method can guarantee a majority in every election, including RCV.

Benefit #3: Decreased Political Polarization

Americans are more polarized today than ever before. A 2019 Pew poll asked partisan voters to rate their feelings towards the opposite party on a thermometer-style scale. The results showed that Americans feel increasingly negative toward the party they oppose. In March 2016, before the election, 61% of Democrats gave Republicans a cold rating and 69% of Republicans gave Democrats a cold rating (a thermometer rating of 0-49). By 2019, those numbers had significantly increased, 79% of Democrats and 83% of Republicans rated the other party coldly.

Yet the results from the bipartisan Battleground Poll from October 2019 reported that 8 in 10 Americans say that "compromise and common ground should be the goal for political leaders."

Ranked choice voting could help bridge America's widening political divide by changing how elections work. This is partly because RCV decreases negative campaigning and partisan politicking. When a politician needs second-choice votes to win, they're incentivized to promote their policies rather than tear down their opponents. And they are incentivized to focus on the beliefs they have in common with other candidates rather than the small policy differences.

In RCV contests, candidates do best when they reach out and positively influence as many voters as possible–including those who support their opponents. This gives constituents more power and major parties less power. With RCV, candidates can't write off any voter as "unreachable"; they must genuinely try to appeal to voters who are openly voting third party. This means that in order to gain those second-choice votes, major parties will have to look at the third parties close to them and adjust their platforms accordingly.

A 2016 study on campaign civility in local RCV elections found that voters viewed campaigns as more civil than they did in cities without RCV. The study concluded that "people in cities using preferential voting were significantly more satisfied with the conduct of local campaigns than people in similar cities with plurality elections." They added, "People in cities with preferential voting were also less likely to view campaigns as negative, and less likely to respond that candidates were frequently criticizing each other."

Our current voting system only does one thing well: fuel America's two-party system, a system that is divisive, outdated, and makes voters feel like their votes don't count. When voters feel like their votes count, they show up and they participate. In the words of Elizabeth Warren, RCV's latest champion, "That's a stronger democracy."

Congratulations, Maine; this is a huge step in the right direction. Now let's hope we see similar changes across America—before it's too late.

It's Time to Stop Gamifying Politics

I fear that we now face our own game of thrones in America. What has been an awful year only looks worse as we descend into a foul mood in advance of the 2020 election. We stand on the brink of dangerous things and very dark times. I think of Spain in the 1930s. That civil war had antecedents comparable to our own situation: social divides along rigid dichotomies, including the rural versus urban, religion versus secularism, capitalism versus socialism, and law versus anarchy. At the end of the day, there were no "good guys," as mass killings of political enemies occurred on both sides. Prosperity and freedom were casualties, alongside hundreds of thousands of lives.

I doubt that such a quick devolution lies in store for us. Rather, I suspect we face a less dramatic and more prolonged devolution, unless we can resolve the philosophical–rather than political–gaps in our own society.

Were our differences only "political," we could understand each other. But we now find that the "political" has become the "philosophical."

In 2020 America we live in basic disagreement about the country itself. On the one hand, those subscribing to the philosophy of the 1619 Project and the BLM movement strongly believe that our country lives a racist lie. On the other hand, those subscribing to the philosophy of American exceptionalism strongly believe that our nation remains a city on the hill and a beacon of freedom for people everywhere. Objectively, we are a house divided, with little ability to compromise.

And now comes the election with high stakes of one basic philosophy crushing the other. Is it even possible to find peace?

At the very least, we can ratchet down the rhetoric. We can agree to refrain from language that demonizes the other side. Simple disagreement, particularly on a philosophical matter, does not require personal animus. But we talk in the most suspicious terms about the intentions of others. We talk about "voting as if our lives depend upon it," which wouldn't be the case if we all refrained from threats, lack of incivility, and actual violence. Demonizing "the other side" with demeaning language and threats only begs for retaliation. It's no wonder that people fear destruction.

We do not hold our politicians accountable for this situation, because those politicians encourage us to continue the cycle so they can ingratiate themselves with supporters

When confronted about civil unrest, politicians blame each other for irresponsible statements and dangerous escalations. They jockey for position as to "who started it" like children in the playground. But, in the end, they do not step back, and they do not de-escalate. Rather, they seem hellbent on inflaming things further in the pursuit of political power.

It's time we stop gamifying politics. Right now, each side sees a zero-sum game, such that one side has the chance to win at the others' total expense, based on how well democracy can be gamed by any means. We no longer trust each other, we no longer extend goodwill, and we no longer want to play by rules, unless those rules are certain to benefit us in the outcome. No one can even agree on the process of voting itself, with grave concerns over the mail-in voting process for 2020.

As de Maistre said, "Every nation gets the government it deserves." The chaos and dysfunction in our politics reflects the chaos and dysfunction in our own polity. We have to decide whether winning at all costs is really the goal. I urge us all to take it down a notch.

I urge us all to focus on processes that unite, as opposed to trying to set up rules that allow us to win. I urge us all to stop with the threats and to extend some goodwill to the other side. I urge more grace in victory and less malice in defeat.

Otherwise, I wish us good fortune in the wars to come.

Margaret Caliente is a professional athlete turned internet entrepreneur and Manhattan-based journalist.Why I Vote (as a Naturalized Citizen)

We're here, and we're growing in numbers.

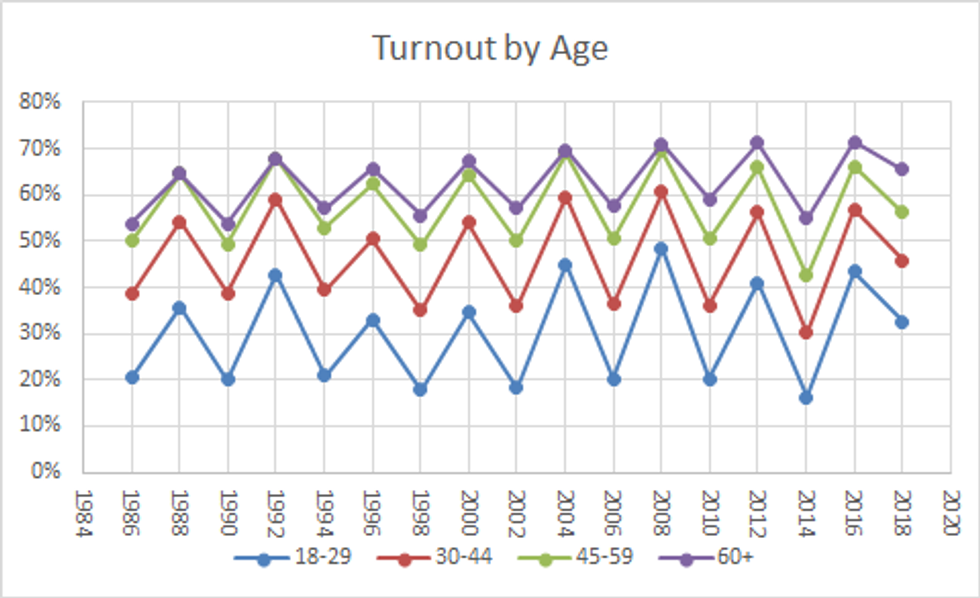

Everybody knows that young people have the lowest voting turnout rates of any demographic. It's a statistic that's often used against us to support allegations that we're lazy, self-involved, and too apathetic to care about the future of politics. For some of us, that's true. But within that 18-29 year-old demographic, there's a community that's too often overlooked.

A recent estimate from Pew Research Center finds that naturalized citizens will comprise about 10% of the eligible voters in the 2020 election–that's about 23 million people, a 93% increase since 2000. That's right: We're here, and we're growing.

The power of naturalized citizen voters shouldn't be underestimated. Generally speaking, voting turnout rates of naturalized citizens are higher than natural citizens. According to Pew, 34% of naturalized citizen voters are Latinx and 31% identify as Asian; in each of those communities, more foreign-born immigrants show up to vote than non-immigrants. Where are these voters located? 56% of U.S. immigrants reside in the country's four most populated states. Of course, these are also the states with the most members of the electoral college: California (55), New York (29), Texas (38), and Florida (29).

It's no wonder why naturalized voter turnout would be high. Even as a naturalized citizen since I was one and a half years old, I can't take my right to vote for granted. Not even my jaded attitude as an academic or an irony-poisoned millennial can make me forget that 55 years ago, people like me were barely allowed into this country, thanks to immigration quotas and plain discrimination. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 eliminated the quota system, and while the new immigration policy still favored northern and western Europeans, the law allowed increased flow of immigrants from Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

Amidst today's immigration crisis under the Trump administration, a growing number of voters are immigrants or the children of immigrants and shouldn't be ignored or dismissed. Even if immigration trends stay the same (rather than increase, as they are more likely to), then today's 10% of voters who are naturalized citizens will become at least 20% by 2040, with immigrants predicted to be the driving force of population growth in the U.S. in coming years.

These numbers impact the turnout of young voters like me and young people's investment in the policies and overall political system, which has turned away people who looked like me and which may turn away those people in the future if policies aren't changed. I'm a naturalized citizen, so I vote.

Should prisoners have voting rights?

Bernie is talking about voting rights, but is this the most important issue facing offenders?

Bernie Sanders has gotten some attention, and a lot of criticism, for proposing that people currently incarcerated, on probation, or parole should have the right to vote.

He even wrote an op-ed about it. Kamala Harris said she supported the idea and then flip-flopped once she realized what a gaffe it was. Vox has an excellent, though undoubtedly "woke" take on the issue here.

This is a legislation that is opposed by 3 out of 4 Americans, which reveals that Bernie is a dangerous, even reckless candidate for the Dems. So many of his views are completely out of line with the mainstream. And we all know who is going to focus on those if he somehow surpasses Biden as the nominee.

Efforts to reform the criminal justice system are vital, but voting rights are just about at the bottom of the list of what matters to offenders. They want access to education and job training and work opportunities that will give them a chance to be productive in the world once they finally get out. The First Step Act was an excellent bit of progress, but there is so much more to do to block the school-to-prison pipeline. Progress is being made at the state level, and there seems to be a bipartisan consensus, aside from Sen. Tom Cotton, to keep reform moving forward.

State by state, offenders need fewer of the tripwires- high bail amounts, fees, fines, drug tests- that get them locked up in the first place or sent back to prison. Overcrowded conditions still abound in so many facilities.

While Bernie dreams of things that few people support, will he draw attention away from needed reform, maybe even turn people against it?

Deceased Brothel Owner Wins Nevada Election: This is America

Dennis Hof won his bid for Nevada Assembly District 36 last night, despite having died three weeks ago.

Midterm elections are often considered a referendum on a sitting administration's progress—a collective report card graded by the people. Early numbers from this year's elections suggest a substantial and possibly record increase in voter turnout, which has been historically low in non-presidential voting years.

It's not surprising, given the turbulent political climate, that candidates from both parties continued to campaign at full speed up until the final hours. Yet despite an election cycle that saw blatantly racist attack ads, felony accusations, and threats of violence, the one surefire road to victory has been apparent for years: death.

Outlandish as it may seem, at least nine dead people have been elected to public office since 1962—six in the last 20 years alone. The latest, Dennis Hof, whose body was discovered last month after the legal brothel owner had celebrated at a campaign-and-birthday party, claimed victory in Nevada last night. Prior to his death, the 72-year-old had been celebrating with friends Heidi Fleiss, Ron Jeremy, and Joe Arpaio.

Ballots Beyond the Grave: Deceased People Who Have Won Elections

Rep. Clement Miller (CA, 1962; airplane accident)

Reps. Nick Begich (AK) and Hale Boggs (LA, 1972; airplane accident)

Gov. Mel Carnahan (MO, 2000; plane crash)

Rep. Patsy Mink (HI, 2002; viral pneumonia)

Sen. James Rhoades (PENN, 2008; car accident)

Sen. Jenny Oropeza (CA, 2010; cancer)

Sen. Mario Gallegos (TX, 2012; liver disease)

Dennis Hof (NV, 2018; cause of death not yet reported)

Hof ran for office as a self-proclaimed "Trump Republican" and stated that the president's 2016 win ignited his own desire for a career in politics. Similarities between the two run deep. Hof gained fame as a reality star on the long-running HBO documentary series Cathouse, which captured life at the Moonlite Bunny Ranch, one of several legal brothels owned and operated by Hof. In 2015, he published a memoir titled "The Art of the Pimp," a clear homage to Trump's "The Art of the Deal." In it, Hof included a psychological profile by psychotherapist Dr. Sheenah Hankin, which categorizes Hof as a narcissist who abused the sex workers he employed.

Among the issues he championed were immigration reform, a repeal of Nevada's 2015 Commerce Tax, and a campus carry law that would allow concealed-carry permit holders to bring their weapons onto Nevada college and university campuses. He was endorsed by Roger Stone and Grover Norquist. In the 2018 primary elections, Hof beat incumbent James Oscarson by a mere 432 votes. Because he died within 60 days of the upcoming election, Hof remained on the ballot, though signs were posted at polling sites notifying voters of his death.

It seems as though these issues matter more than electing a living person to citizens of the 36th Assembly District. In fact, a 2013 study by Vanderbilt University found that, in lower-level elections, voters are most likely to elect the candidate with the highest name recognition.

The 36th Assembly District, which spans Clark, Lincoln, and Nye counties, has long been a GOP stronghold. Hof defeated Democrat Lesia Romanov, a first-time (living, breathing) candidate and lifetime educator who works as assistant principal of an elementary school for at-risk children. Romanov was impelled to run for office by a desire for common-sense gun reform following the mass shooting in Parkland, Florida. Yet, too many of her constituents, upon discovering she was running against Hof, she became a de facto advocate for women, including "survivors of sex trafficking and exploited and abused brothel workers," according to NBC News. Romanov was among many women running for office in hopes of making Nevada's legislature the first to hold a female majority in the country.

As The Washington Post reported in 2014, there hasn't been an election with a dead person on the ballot in which the dead person lost. It's hard to determine what's more damning for American democracy: that voters are so divided that they're more likely to vote for a dead person than cross party lines or that they've been voting that way for years. At the same time, one might argue that giving Hof's seat to a living Republican (as appointed by county officials, according to state law) is a better outcome than if it'd gone to Hof himself, considering his history of sexual abuse allegations. The most preposterous indictment of the American political system is that although deceased candidates have been elected before, now the electorate could seemingly ask itself—in all seriousness—whether a dead serial abuser makes a better candidate than a living one. And no one seems to know the answer.

What you need to know about voting systems around the world

How the voting systems around the world differ from country to country

There are many different voting systems in the world that vary in large or small ways from one another. Here are some of the most popular, explained. These three systems make up the majority of the world's election processes and can be used for larger and smaller elections.

First, some vocab

Plurality: The Candidate with the most votes wins, doesn't need to be a majority.

Examples: United States, United Kingdom, Ethiopia, India, etc.

Two Round System: Similar to plurality but a winner needs the majority. If there is no majority in the first round of voting then there will be a second with the 2 leading candidates.

Examples: France, Iran, Mali, Vietnam, etc.

List Proportional Voting: Multi-winner system where political parties nominate candidates and electors vote for preferred party or candidate. The governmental seats are given to each party in proportion to the votes they receive.

Examples: Spain, Morocco, Russia, Brazil, Angola, etc.

A Deeper Look into Certain Election Processes

France

French Presidents serve for 5 year terms and are elected using a runoff voting system which involves two rounds of elections. If someone doesn't win the majority in the first round then the top contenders run against each other in the second. France does not have a two party system and many different parties are represented in their 3 branches of government. This means that the French President could have a Prime Minister from another political party.

Both the financing and spending of French campaigns are highly regulated. All commercial advertisements are prohibited in the three months before the election. Political ads are aired for free but on an equal basis for each candidate on national television and radio. There are limits on donations and expenses that are regulated by an independent financial representative of the campaign.

United Kingdom

General elections are held every five years with a large number of elections across the UK. In 2015, six hundred and fifty people were elected into the House of Commons and this greatly changes the standing of the parties in the government. With three major parties there is no longer a two party system. These parties are the Conservative Party formerly know as the Tories, the Liberal Democrats formerly known as the Whigs, and the Labour Party who all make up the bulk of the government along with various independents.

The party that wins the majority of seats in the House of Commons in the general election becomes the leading party. The leader of the majority party is appointed Prime Minister by the Queen. The leader of the minority party is referred to as the leader of the opposition. The Prime Minister appoints the ministries and forms the government. There are moments where the system is adapted whether the Prime Minister calls for a special early election or there is no party with a majority in the House of Commons.

UK elections limit how much campaigns can spend during certain elections, but there is no price limit for donations. This is regulated by the Electoral Commission which is an independent regulatory body. All of the parties need to keep records for the independent audit. To ensure transparency the Electoral Commission publishes party spending returns online.

Russia

A presidential candidate can be nominated by a Russian political party or by a collection of signatures in support. Similar to France, Russia has many political parties that make up their government and there is also a two round voting system. The Presidential term is 6 years and though someone can hold many terms there can only be two consecutive terms at a time. There were protests and concerns over the legitimacy of past elections.

The main political party is the United Russia Party lead by Vladimir Putin and it holds 343 seats of the 450 possible seats in their governmental body, the Duma. Other parties are the Communist Party, the Liberal Democratic Party, A Just Russia, Civic Platform, and there are independents. Members of the Duma are elected for 5 year terms.

Though spending and broadcast time is monitored and regulated there are large loopholes for the party who is in control of public resources. Opposition parties need to fund from their own resources but United Russia uses official state-funded trips, positive news reporting, and other means to avoid using personal funds.